- Home

- Trevor Shearston

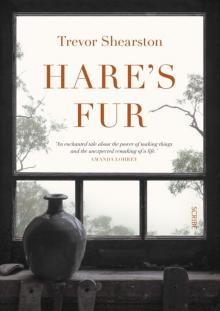

Hare's Fur

Hare's Fur Read online

Contents

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Hare’s Fur

Hare’s Fur (cont'd)

Acknowledgements

HARE’S FUR

Trevor Shearston is the author of Something in the Blood, Sticks That Kill, White Lies, Concertinas, A Straight Young Back, Tinder, and Dead Birds. His novel Game, about the bushranger Ben Hall, was short-listed for the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards, Christina Stead Prize for Fiction 2014, long-listed for the Miles Franklin Literary Award 2014, and short-listed for the Colin Roderick Award 2013. He lives in Katoomba, in the Blue Mountains.

Scribe Publications

18–20 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

2 John St, Clerkenwell, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

Published by Scribe 2019

Copyright © Trevor Shearston 2019

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

9781925713473 (Australian edition)

9781925693553 (e-book)

A CiP entry for this title is available from the National Library of Australia.

scribepublications.com.au

scribepublications.co.uk

For Bette

The workshop air was clammy with the overnight breath of clay. He walked to the racks and felt the feet of three of the run of bowls he’d thrown a day back. They were close to leather-hard. With the fire, they’d be ready to turn by afternoon. He crouched at the cast-iron stove and laid gumleaves and twigs on the bed of ash and lit a leaf. When the twigs, too, caught, he added pine splits, closed the door, and spun the air vent full open, hearing the sound he’d loved all his life of a fire leaping to obey.

The stove was too slow for coffee, he brewed a pot on the small electric hotplate. The mug was the last he owned of Seth Bligh’s high-fired earthenware. It belonged on a safe shelf in the kitchen, but he continued to use it. As Seth would have wanted. Pots fine enough to keep, cheap enough to drop had read the sign on his lorry. The man would have been amazed, even horrified, by the price Russell could now ask for a single tea bowl. He drank standing at the window to the right of the wheel and looking out into the bush. Almost everything had finished flowering except for the fringed blue ones that looked like orchids but weren’t, and the mountain devils, which put out a few red cups whatever the month. He should have known the name of the blue ones, too, she’d told him more than once. He needed to check the fences around her orchid colonies. And quite suddenly he was in tears, had to stand the mug on the wheel-head and dig in his pocket for a hanky. She would never again paint them, the wallabies could have them. ‘No! You damn-well look after them! This afternoon!’ He balled the hanky, shoved it back into his pocket.

He went outside to the annexe. Its end wall and half the long side were glass, cobwebbed and spattered, ten glazed doors he’d got cheap at a demolition auction and screwed upright to a timber frame. He walked to the last in the row of bins. He’d checked label and clay yesterday, pinched out a piece and worked it in his fingers. Stored unopened for a year, it was well soured, would hold the big forms he wanted. He pulled out the plastic sheeting he’d tucked loosely back in. The four balls were furred with algae, giant cabbages, their stink rising around him as from a pond stirred with a stick. He clamped a hand each side of the top ball and straightened, spun, and dumped the ball on the wedging table, the pull in his lower back drawing from him a grunt. He dumped the second beside the first, then tucked the plastic tightly around the remaining two balls and lidded the bin.

He had watched Chinese and Japanese potters wedge, and, to satisfy his curiosity, emulated them, but at his own table he wedged as he was taught at sixteen by Seth Bligh, passing on the methods and lore of his native Devon. Five minutes and the clay came alive, had spring under his thumb. He wire-cut and weighed out six three-kilo chunks and kneaded and balled them, rolling each to the back of the table. Then, arms and shoulders needing a rest, he walked to the opening in the side wall and stood breathing white blooms at the bush. He was ageing along with his clays. But he was no longer cold. He returned to the wedging table and made up six more balls, then transferred the balls to boards and began ferrying the loads into the workshop and piling the balls on the benchtop to the right of the wheel. Already he could feel the difference in the air. The pine splits had burned down to ember. He added more, then a chunk of ironbark, and closed the vent to a whisker. He needed the room warm, not hot. He carried the now burbling kettle to the wheel and topped up the slurry bowl into which he’d be dipping his fingers. It was time he settled.

He wanted eight large bottles for the risers directly behind the firebox. He could see the form, the weight towards the foot, yet with shoulders to catch the fly-ash that gusted through the kiln and would melt and run. Thicker walls than he’d usually throw, the heat there massive and prolonged. Half might survive. He’d settle for half.

The wheel stood between the two western windows, in an embayment in the bench. It was his oldest friend. He’d made it himself, at eighteen, its design identical in every respect to Seth Bligh’s, but its timber mountain ash, the staple framing tree at the mill in Blackheath where he’d first encountered the man. He’d replaced the crank and chain, the flywheel bearing twice, and the saddle pad more times than he could remember. But the wheel was the same, his first and only.

He took a dozen plywood batts from the rack where they stood like unsleeved LPs and placed the stack within reach when he sat, then snatched up a handful of clay from the waste bucket on the floor and roughly balled it. He hoisted himself into the saddle and slapped the ball onto the centre of the wheel-head, kicked the bar to set the wheel spinning, and, pushing down and out with his thumbs, worked the clay into a thin pad to take the batts. When it was level he stopped the wheel and picked up a batt and the sponge. He dampened each side and dropped the sponge back in its bucket, then positioned the batt on the pad and hammered around its rim with his fist to seat it.

He swivelled and with both hands lifted the first of his throwing balls and slapped it onto the batt, then set the wheel spinning again and slurried his hands and drew the clay up into a cone, feeling it centre. He pushed down, coned it again, and again pushed down, then opened a well in the clay with his thumbs and formed the floor of the bottle. He inserted the fingers of his left hand into the well and, their pressure opposed by the crook’d index finger of his right on the outside of the ball, pulled the clay up into a thick-walled cylinder, his torso rising in unison on a long slow inbreath, his elbows flaring. He leaned and reinserted his hand and wrist and repeated the pull, drawing the cylinder higher and thinning the walls, then re-slurried his fingers and on the next pull formed the belly and shoulder and collared the top, leaving enough fatness for the neck. He let the wheel coast and cocked his head and studied belly and shoulder. Satisfied, he drew up the neck and gave it a rolled rim, then reached to the slurry bowl for the strip of soaking chamois to smooth the lip, its touch slicker than any finger.

He slowed the wheel and leaned back and to his right, hands withdrawn, but not yet dismissed. What he’d seen in his mind now existed. He was pleased in particular by the curve of the shoulder, mirrored in reverse where shoulder met neck. ‘You’ll do,’ he said modestly. He brought the wheel to a stop and laid the chamois half-submerged again in the slurry bo

wl, reached for the wire and made the shrinkage cut between batt and bottle base, then levered the batt from the wheel-head, lifted it in both hands, and, twisting from the waist, slid batt and bottle onto the left-hand wing of the embayment. Twisting right, he plucked the sponge from its bucket and squeezed it out, picked up a fresh batt and dampened its faces, then positioned it on the clay pad and hammered round its rim, so much of his working life this endless unconscious repetition.

He’d been embarrassed the first time a reviewer called his throwing ‘masterful’. Adele, though, had protested hotly, ‘Of course it is! And you know it.’ After she retired, she would ask him at breakfast what he was doing that day. If he was going to one of the many jobs she referred to as ‘drudge’ — blunging clay, mixing and sieving glaze, chipping dags from kiln shelves — he wouldn’t see her. But if he was throwing she would get through her watering smartly and arrive at the studio with her knitting and sit in the more comfortable of the two ancient plush armchairs. They would talk companionably between pots, and on into the positioning of the next ball on the wheel-head, but when he began the throw proper, fell into communion with the clay, she would still the needles and her tongue. She was witness to the decades of practice that informed every throw, but had never tired of the magic — the bud-opening of ball into bowl, the shining rise of the cylinder that bellied into a blossom jar. He’d offered once, not long after they were married, to teach her. He still remembered what she’d said in dismissing the offer. Once I start I might not stop, and we’ll have a rivalry on our hands.

After six bottles his lower back was protesting. He slid backwards from the saddle, put hands on hips and swivelled, feeling the discs crackle. He walked to the stove and floated a hand above the plate, then, keeping his back straight, stooped and spun the vent a turn. It was too soon for another coffee. Instead he filled a mug from the thermos of tank water. He stood sipping while he studied in turn each of the six bottles, looking for the flaw he’d missed when he lifted it from the wheel-head. Only one did his eye return to, the curve of the belly a shade too even. His hands rose towards it, then he lowered them. It wasn’t ‘bad’. But if when he’d thrown all twelve he had his eight, this would be a cull. The law he lived by was implacable. No glaze, no fire effect, could redeem a dud throw. His gaze went to the two yellowed filing cards pinned on the wall between the windows. He no longer remembered why he’d used a pencil. Probably because in his excitement to get the words down he’d grabbed whatever was to hand.

About form. I am sure that the forms of the most common, everyday utensils can evoke so much that is inexpressible in any other language, about humanness. That with only the very slightest gesture, the merest suggestion of the lip of a jug, or pouring spout, or the lightest softening of a curve, there can be expressed a sort of vulnerability, or a tenderness, or an attentiveness that causes us to pause. That the scale alone of some objects can touch us, and a small jug of open and generous form can somehow seem brave and absurd and a bit like ourselves.

The last words never failed to move him. The second card expressed his own inarticulateness about what he did.

Words get too big. Leave them.

Both quotations were from an essay by Gwyn Hanssen Pigott. He hadn’t till then known she could write as well as she threw. He still wondered why, having written the first, she had gone on to write the second. He had also, standing here, wished he’d made the effort to meet her. Too late now. Also dead of a stroke. He closed his eyes, whispered, ‘Oh, love.’

He’d been on the wheel, but turning. If throwing, he let the phone ring. He thought it would be Hugh, wanting to pick up the splitter. A woman said, ‘Mr Bass?’ The reluctance chilled him, made his ‘yes’ sound cagey even to him.

‘Mr Bass, this is Emergency at Katoomba Hospital. We have your wife here and we’re —’

‘Yes, I’ll speak to her please!’

‘Your wife’s unconscious, Mr Bass. She’s had a fall and hit her head.’

‘I’ll be ten minutes.’

He went as he was, entering the house only to grab his wallet and the ute keys. The receptionist ushered him immediately through triage to a waiting nurse. She conducted him to a cubicle and parted the curtains. Two more nurses and a man in blue surgical gloves glanced round from what they were doing. Breath left him. The nurse cupped his elbow and asked if he needed to sit. He shook his head, but she retained her grip, came with him to the gurney. He didn’t recognise the Adele who’d come to the workshop door to say she was going shopping. Her head was encased in bandages, her closed right eyelid and her cheek were black and swollen. A breathing tube was taped into her mouth, thinner tubes ran to and from both forearms. A machine on a stand was emitting a loud beeping. He lifted her limp right hand from the coverlet and enfolded it in both of his. Its coldness terrified him. A chair nudged the backs of his knees. The man came round the foot of the gurney. ‘Sit, Mr Bass, please. I’m Dr Dowlan — Edwin.’ He had a faint accent Russell did not recognise.

The doctor told him they believed, from what witnesses had told the paramedics, that his wife had suffered a stroke while carrying shopping to her car. Unfortunately, in falling she’d hit her head on a concrete divider. They had not yet done an X-ray, but suspected a skull fracture. He asked what pre-existing medical conditions she had, and Russell told him, Type 2 diabetes. The man frowned. ‘Unusual in someone with her light build.’

‘Yes.’

‘You’d have known, I take it, of the predisposition to stroke?’

‘We both did.’

‘Of course.’

The X-ray had confirmed the fracture, blood tests the stroke. She’d died that night not knowing he was there.

He could fire the glaze kiln by himself. The tunnel kiln, the anagama, he would never fire again. He couldn’t fire it alone, not for seventy hours, and if not with her then not at all. He’d stood at the firemouth a month after she died and spoken the promise aloud.

He threw the rest of the bottles. He squashed three, including the one he’d provisionally sentenced earlier, and dropped their clay in the recycling bin. The remaining nine he transferred to the racks. He checked that the heater had wood, then went outside to the tank and rinsed his hands.

He wasn’t especially hungry, but cut bread and cheese and quartered a tomato. He hoped Delys was cooking a roast, not a thing he went to the bother of anymore for just himself. He’d had a second coffee over in the workshop. Another and he’d be flying. He settled for an apple.

He nibbled its last frills of flesh standing on the workshop apron. Once, he’d have then strolled over to the chook run and lobbed the core over the wire to watch the mad scrabble. But only when Adele wasn’t home, or he knew he wouldn’t be caught. When she still worked it was part of his morning to chuck them a cup of cracked corn and collect the eggs. But they were hers, ‘my girls’. Delys had found someone to take them. Partly from guilt he avoided the empty run. A flick of his wrist sent the core bouncing out onto the grass where a currawong would find it.

Keeping an eye on the clock, he turned the feet of the four boards of bowls. After sliding the last board onto its dowels, he ran his eye again along the row of bottles, decided two more might be for the chop.

He took off his clayed trousers on the landing and went inside to the bedroom and pulled on trackpants. The phone rang as he walked back through the kitchen. He let it go to the machine, but stood listening, and whoever it was hung up as soon as his voice started. It used to be hers, and he’d left it for months, the thought of wiping her too painful. In the laundry he took down from the shelf the paintbrush and cloth, then reminded himself aloud that he was going via the orchid colonies and pocketed some twist-ties.

She’d done her doctorate in her early forties, on the biological mechanisms governing fire sensitivity in native terrestrial orchids. They’d travelled together to the south-west of Western Australia, to the Grampians, the Flinders Ra

nges, Tasmania. They were not places thick with potters, and he let pottery go when they travelled, was content to hunt orchids. But, for him, once to each place was enough. She went alone on the repeat visits timed to the change of seasons and for which she had to apply for study leave, and the adventitious ones following major fires in Gippsland and the Adelaide Hills, which the Gardens were happy to pay for, hoping they would never have to cope with the same catastrophe, but wanting their own expert on hand if ever they did. From plants collected on her trips, and from locally in the Mountains, she had established on their own half-acre colonies of fire-tolerant and fire-loving species to study, photograph, and paint. In the bedroom hung watercolour portraits of spotted doubletails and the large duck orchid, in the kitchen the veined sun orchid, all painted from blooms in the colonies he was walking to. A pad that wound among the trees linked the colonies, starting behind the workshop and merging with the track to what they’d christened, when Michael was a toddler, ‘picnic ledge’, now anything but that. Most of the species would have died back to their basal leaves, some underground to tubers, but he hadn’t inspected the fences since summer and knew himself well enough to know that he might neglect to do so until next summer, when for some it would be too late, their shoots cropped by the resident wallabies.

At the start of the pad, he stopped to pull a cotoneaster and two young holly. Deeper in, the weeds disappeared, shaded out by the thick understorey of tea-tree, acacias, and hakeas, and the even denser ground covers, grevillea laurifolia, dillwynia, hibbertia. The earth was dry and hard, leaves crackling beneath his soles. The first colony was some thirty metres in. Its circular fence of black plastic mesh was intact. It bore no identifying labels — she not needing any — and he no longer remembered what species it enclosed. At the next, a stake had rotted. He found a strong stick and pushed it into the soil and hitched the mesh to it with a twist-tie. The last colony he knew — red beardie — not because it was in flower, but because of its neighbour, a large mountain devil which the wattle birds ransacked in the leaner months, scattering flower debris around its base in a red pool. Nothing of the colony was visible, the plants gone underground. He resisted for once his growing habit of thinking aloud, refusing to be openly maudlin.

Hare's Fur

Hare's Fur