- Home

- Trevor Shearston

Hare's Fur Page 3

Hare's Fur Read online

Page 3

‘I know.’

Hugh lifted the daypack from the floor and held the straps for him to insert his arms.

‘When do you need the splitter?’ Russell said. ‘I’m still a month or more away.’

‘I mightn’t. Got a good bit stacked. Not in your road, is it?’

‘No. And I’m thinking I’ll go down the valley tomorrow. The usual, I’ll ring that I’m back. So, next week. Or sooner if you want the splitter.’ He wouldn’t see Delys, she stayed home and read. He reached for and squeezed her hand, the words she’d spoken still between them. The dog, too, was waiting to say goodbye. Russell ruffled the thinning hair on the scalp, drew his fingers up one velvet ear.

He had returned to his young man’s habit of sleeping with the curtains open, was up before the sun. He filled a glass at the sink and stood as he did every morning, absently drinking while looking out to judge how cold it had got, what the sky promised. Rags of mist hung in the gums behind the workshop. The grass sparkled, again only with dew. But his breath was visible, made a circle on the pane. The small blow heater she’d insisted on buying for the kitchen was still where it lived, behind the pantry door. He hated the noise of the thing. A month or so, though, and he’d be forced to bring it out in the mornings. He turned mechanically to the row of saucepans hung from hooks before his mind’s voice cut in, said not to waste time on porridge. Throw the teapots he’d agreed to, then get down to the creek. He fried two of Delys’s eggs.

The air in the workshop was cold, his breath pluming, but he didn’t go immediately to the stove, he went instead to the racks and felt the feet of two of the bottles. Not ready — he could do just the teapots and leave. He couldn’t do anything, though, until he’d lit a fire, and had a coffee. He used bark and twigs, added pine splits and, when they were ablaze, a light chunk of yellow box. Starved of air, a small fire would be safe to leave. He brewed the pot on the electric hotplate, drank it from Seth’s mug. Then he went out to the annexe. He’d promised four, would throw eight. He wedged and balled the clay and carried the balls, and a larger ball for the spouts and lids, piled on one board, back to the workshop. He’d stopped making teapots — too fiddly and time-consuming, and the form itself had lost its interest — but the unspoken bargain with Geoffrey at Clay was that he agreed to the occasional group show in return for his solo ones. Not that he any longer needed the money from either. The house was years ago paid off, he qualified for a part-pension, and her superannuation resided now in his account, far more than he could envisage ever spending. He’d had the same conversation with Hugh, that when they were younger and really needed to sell what they produced, they couldn’t get prices that gave them a living. Both were forced to teach. Now, their reputations made, they could command the prices but no longer needed the money. He remembered the curl of Hugh’s lip. ‘Tell them all to get fucked, shall we, and retire!’

He threw a full-bellied teapot, then measured and threw its lid, set each on a batt and pulled from the larger ball a chunk and balled it in his hands, and threw a spout. He cut the spout from the wheel and stood it upright beside the pot, to attach tomorrow. He was aware as he threw that he wasn’t totally engaged, in a part of his mind already down in the valley. Even so he made no mistakes, at the end of two hours had eight he could live with.

His old canvas A-frame hung with the hats on the row of hooks on the landing wall. He carried it into the kitchen and sat it on a chair and went to the bedroom, returned wearing his down jacket. He made a plunger and filled the slim hiking thermos and stood it in the pack. He washed an apple and a pear, wrapped them in a tea towel and pushed the bundle into the pack to jam the thermos upright. A handful of dates, another of almonds he dropped into a clickseal pouch, which he pushed into the side pocket of his jacket. He drew the pack’s drawstrings, but didn’t tie them. He hoisted the pack by its straps and walked out to the landing and sat on the woodbox and put on his boots. The cherrywood staff she’d bought him for his seventieth beckoned from the corner of the landing. He turned and went down the steps and walked across the grass to the annexe. The folded leather ore bags were on the bench beside the ball mill, the geologists’ pick on top. He worked the bags through the mouth of the pack, then pushed the pick handle down beside the thermos till the head nestled on the bags. He tied the drawstrings and buckled the flap, then shouldered the straps and walked along the corridor between the kilns, the most direct route to the road.

He was going into the valley to the head of a nameless creek where, at a dyke, he filled one of the leather ore bags with decomposing basalt. Crushed and ball-milled and fluxed with ash from the workshop stove, the stone gave him a fat and very black temmoku breaking to rust or sometimes to a piercing blue, or, when saggared for heavier reduction, the streaks of brown called hare’s fur. The second ore bag he filled with splinters he broke with the pick from a seam of milky-green rock which, fluxed with the same ash, gave him the unctuous grey-white called guan that somewhere in every firing blushed a delicate pink he’d never sought to analyse, but simply accepted as a gift.

The walk was work, but it was also a meditation. After she retired Adele had occasionally come with him. Then it was not a meditation but a continuation of the long conversation that was their marriage. And it was slower going, especially in spring, for she was constantly darting off into the bush to photograph a possumwood in flower, or an orchid she’d spotted. He was generous with what he’d learned in the fifty-six years since he’d thrown his first pot. To a fault, as she’d many times told him. But he had never publicly disclosed the source of his two signature glazes. Nor had he ever invited Hugh to come with him, and Hugh, knowing why, had never invited himself. For he had found the dyke and the seam on one of the solitary grieving walks he’d done, incapable of work, after Michael’s death. The creek was a place he could share only with Adele. Now, no one.

Tea-tree and lomandra had grown across the opening of the abandoned lookout. He pushed through the clumps of blades to the apron of lichened concrete and found the faint pad that only his feet maintained, skirting to the right of the platform through wind-sculpted casuarinas and hakea and more tea-tree to the cliff edge. There he stopped and removed his beanie and took the sun on his face and scalp. It was the last direct sunlight he would know until he stood again on this spot. He put his beanie back on, then, parting the shrubs like a swimmer, advanced till he was at the top of the near-vertical cleft that some fool many years ago had christened, in lead undercoat, Devil’s Well.

After thirty or so of the deep stone steps his knees began to jelly, but he resisted reaching to the rusted chain laced to the cliff face, not trusting the ancient concrete that plugged the piton holes. A trickle of water entered invisibly on his left, its tinkle the only sound but for that of his boots and his breathing. Cold air rose up the cleft as if up a ventilator shaft, carrying the paradoxical odours of mossed stone and dust. A yellow-breasted robin joined him, flittering above the rasp ferns. The bird stayed close, hunting for moths or flies disturbed by his passage. Russell didn’t see it take one, and near the bottom of the cleft, where the glen widened, it gave up and disappeared, the air too cold yet for insect wings. The widening was a stone patio that looked down into the continuation of the glen. The slab had once slid from the rock face, but would slide no further, staked in place by three massive coachwoods, their bark grown onto the stone. The trickle was louder, further down becoming a creek, which was joined by another running from the falls below his house and on down to the valley floor to be met by ‘his’ creek.

He halted and dug the fingertips of both hands hard into the hollows of his right knee. From somewhere below, sounding closer in the cold air than they probably were, a male and female whipbird were doing their antiphonal trick, the call and response like a single bird. He could mimic the whistles of rosellas, bring them to the wattle behind the kilns peering down at him in bewilderment. But this call was impossible. He bent and straightened his knee

, then started down the scree.

He followed the creek now, the light a deep green, the track almost obliterated by the ploughing of lyrebirds. He’d been here so many times he recognised individual trees. When he reached the junction he stood looking up into the jumble of car-sized boulders from beneath which ‘his’ creek emerged. The ford was a line of mossed stones where the creeks joined. Two-thirds across he crouched to drink, the water tasting like licked steel. Still crouched, he reached into the flow and picked up one of the black pebbles that so long ago had told him that a strongly iron-bearing rock was shedding into the creek. He could have made a load from the pebbles scattered in the shallows, but that would have meant a wet ore bag. Anyway, he had to walk in to the seam that gave him his guan. He rose and stepped the last three stones to the tiny beach. Against the bank was a black log once adzed flat for a seat. Terraces of orange fungi climbed its sides, rotted wood spilled from its heart. He propped on his buttocks and pulled from his pocket the pouch and ate two dates and some almonds. A sign once nailed to a coachwood now leaned against its base, the words illegible but the arrow chiselled in the timber still visible. One day to satisfy his curiosity he’d obeyed the arrow and found that a junction with the well-used and maintained National Parks track to Helga Falls was only ten minutes away. He stepped round to the back of the log and parted the callicoma growing in a curtain. Here started the pad that ran up the left-hand side of the creek and on which he’d never seen a boot print other than Adele’s or his own.

The pad climbed on tree roots to a low ridge, dropped to the creek, then climbed again steadily into the boxed canyon until he came in sight of what he called the ‘cape’, a bluff of raw sandstone, with caves and overhangs visible around its base. He’d never had the inclination to explore them. If Michael had lived they might have done it together. Rocks from its face had tumbled as far as the creek bed and in places offered the only, but unstable, footing — why he was watching where he placed his feet.

And so saw it, lying between two rocks, a wrapper. A lolly wrapper.

He halted and stared, not quite believing his eyes, then bent awkwardly in the pack and plucked it up. It was so new it crackled. Mars bar. The crimped seal was intact, the cellophane ripped open in a ragged spiral. He raised it to his nose. The smell of chocolate was fresh. But the white inner skin, he saw, had a sheen of moisture. The wrapper had lain overnight. Currawongs picked up shiny things, but would have discarded this as useless long before flying over here. From a light plane, then? Or a chopper? Both crisscrossed the valleys. He knew he was clutching at straws. The wrapper had been dropped from a hand. But going where? There was nowhere. To the head of a nameless creek at the end of a blind canyon. Without a reason like his who would bother?

He crumpled the wrapper, but it refused to ball. He stuffed the springy thing into his jacket pocket — and froze when there came the ring of something hollow and metal against stone, followed by a shrill giggle, a child’s.

He held his breath but the giggling didn’t come again. He breathed into his palm while he slowly swivelled his head. But both sounds, he was sure, had come from just upstream. There was a small pool on the other side of a fall of boulders that had, eons ago, partly dammed the creek. On days in December and January he’d sat on its gravel beach and paddled his feet. Even in midsummer the water numbed them in seconds, his boots feeling weirdly too big when put back on. No one could be paddling at this time of year.

He pulled off his beanie and stuffed it in his pocket, the grey of his hair less conspicuous. Then he chose a route, marking to himself rocks that looked wedged. Using fingertips as feelers he crept up the dam wall, every few steps cautiously straightening to determine whether he could see the pool.

The giggle came again, more subdued, and again he froze. It was followed by a voice, answered by another. Both voices were young, but the second older than the first. He couldn’t make out words, but they carried the earnest tone of children deciding rules. There came the hollow clunk of a stone dropped into what might have been a kettle. He heard the metal thing scrape, then a light splash. He couldn’t just stand guessing. He hunched and in five careful steps reached the spillway down which the water from the pool fell. He slowly raised his head and through the leaves of a shrub got a glimpse of a yellow shirt or jacket, and above it something red, a cap or beanie. If he climbed a further step, keeping the same shrub between him and the pool, a rock bare of moss would give him a clearer view. The pack was unbalancing him. He carefully shrugged the straps from his shoulders and lowered the pack into a cleft between his feet, testing that it was jammed before lifting his hand. He ducked his head and placed his foot and brought the other to meet it, then laid both hands flat on the boulder from which the shrub appeared to grow, and levered himself up, not sure how close he would find himself to the speakers.

They were on their haunches on the hump of rock which divided the beach, the width of the pool between them and him. The shrub’s foliage was sufficiently dense that he had to sway his head to see. The owner of the shriller voice was a boy about five. The other was a girl he guessed to be eight or nine. Both wore trackpants and cheap unpadded windcheaters, the boy’s yellow, the girl’s blue. The windcheaters were filthy. He was reminded of the engrained filth in the windcheaters of the men and women who rummaged through bins in Katoomba Street. A small aluminium saucepan with string tied to the hole in its handle floated at a listing angle on the pool. The other end of the string was in the boy’s hand. The stone he’d heard dropped into metal had been, he guessed, to correct a worse list. The gazes of both were locked on the saucepan. It drifted for a moment before the current caught it, carrying it towards a log around which the water purled.

‘Pull it, you little shit!’ the girl ordered.

The boy instead paid out slack, allowing the saucepan to sail further into danger. But when she half-rose he gave the string a delicate, practised jerk, and the saucepan spun out of the current and back towards the beach. She thrust out her hand for the string.

‘Give it.’

He’d been intrigued by the game, but now he studied the faces. They lacked the roundness of children’s faces, looked bony, underfed. The boy was olive-skinned, his cheeks burnished like — again — those of the bin-rummagers in town, and probably from the same cause, sun and wind. Enough of his hair showed from under the beanie to reveal that it was dark brown. The girl’s face, by contrast, was pale, almost drawn. She was bareheaded and blonde. He had assumed from her coarse familiarity that they were brother and sister, but now was less sure.

She leaned and snatched the string and he saw that behind her, lying on its side, was a blue plastic nine-litre bucket, its handle lashed to a thick stick snapped at both ends. They weren’t on a picnic. He looked beyond them, searching for a shape or colour that might be a tent. There wasn’t one, or it was out of sight. His gaze returned to the puzzle of the bucket. You didn’t carry a bucket to camp overnight. On foot, you didn’t carry one at all, or if you did, a canvas one, not rigid plastic. Both of them looked to be school-age, but the girl certainly. As far as he knew it wasn’t holidays. Not for the Kent kids anyway. The day before yesterday he’d passed them coming home on their bikes, both in uniform.

The girl was bringing the saucepan in hand over hand, like landing a fish. The game was over, he hoped — they’d fill the bucket and go. He could watch where they went. The parent was a fool, sending a boy this size to be on the other end of nine litres of water. And for walking past the creek junction, water at your door, to pitch camp somewhere in a jumble of boulders and forest. The girl was lifting the saucepan from the water. He waited for her to tip out the stones. Instead she held the saucepan level and reached in. She was adjusting the ballast. She bent again to the surface of the pool and relaunched the saucepan, a controlled flick sending it out towards the current while she paid out string. He lowered his head, said into his chest, ‘Shit!’ A splash made him look up. T

he boy had fired a pebble whose ripples were rocking the saucepan, and would have fired another except that the girl slapped it from his fingers.

‘Don’t. I didn’t spoil yours.’

‘But you’re havin two!’ the boy whined.

She ignored him and whipped the wet string to turn the handle to face upstream. Would the game go on until whoever needed the water came looking for them? The only way of getting upstream was past the pool. Not that he’d explored alternative routes, never having had to. But the canyon was too narrow for there to be any — none, certainly, where he’d be both unseen and unheard. He could crab to his left, then stand. But they would bolt, he was sure, the second he showed himself. It was the feral in their appearance, the filthy windcheaters, the slightly starved faces. And they were too at ease, like kids playing in their own backyard. They would react as if to an intruder. Which he was. If they were actually living close by.

He glanced up towards the cape, but most of it was hidden by the upper branches of the shrub he was using as a screen. The logical place was one of the caves. But who would bring children to live in a cave? And why! Clearly they didn’t want to be discovered, whoever they were. Perhaps desperately didn’t want to be. Even if he waited for the children to tire of their game and fill the bucket and leave, he couldn’t continue on to the head of the creek and blithely start chopping stone. The ring of hardened steel would bring him company in no time. His obvious age, and the innocence of his reason for being there, might not be adequate against someone too crazy or too frightened to believe him. And a geologist’s pick, although a perfectly good tool, would make a clumsy weapon.

The boy was whining again to be given a turn. If he waited, maybe whoever was on top might come looking, or at least yell. He’d know, then, who he faced. But that still didn’t mean he’d be able to fill his bags.

‘You can’t,’ he whispered. ‘Not today, anyhow.’

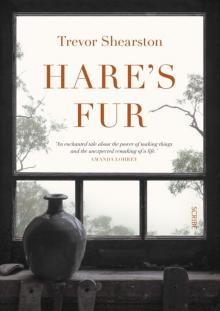

Hare's Fur

Hare's Fur