- Home

- Trevor Shearston

Hare's Fur Page 6

Hare's Fur Read online

Page 6

‘If you want. It won’t be very interesting though.’

The young ones led the way to a crossing higher up. On the other side of the creek was the pad his own feet had made and kept open. The two took off and soon vanished. He offered to Jade that she go, too, if she needed to keep an eye on them. ‘No, they’re right.’ Once, pretending to follow a rosella, he glanced and caught her looking to their rear. Still not entirely sure about him, then. He quickly faced forward as her head began to turn.

They heard the young ones before they saw them. They were crouched each side of the green vein, Emma using a heavy ovoid pebble for a hammerstone, the boy picking up the slivers and piling them on a cushion of moss. He winced when he got closer. In violation of his deep respect for materials, the working face was white with shatter lines. How could they know? They were pleased with how much they’d already broken. He apologised for not having told them he wasn’t taking this rock today, they were going further up. But he would take their pile the next time he came.

They hadn’t explored beyond the vein of stone, believing this to be where the pad ended. But the boy and girl quickly found the break in the ferns and were gone again, not knowing where they were going, but possessed of too much energy to trail along at his pace. He and Jade found them a hundred metres on, at the foot of the cliff, standing bushed in the jumble of boulders roofed by tree ferns and struggling coachwoods. The girl opened her hands, nothing here. He lifted a finger towards the ledge over which the newborn creek ran after emerging from the cliff face.

Compared with bashing stone to splinters, the dyke was dull. He held open the leather ore bag while the young ones scooped up handfuls of the grey-black crumbs spilled onto the ledge and took turns to pour them in. Jade skirted the spill and walked to the face of the dyke and, with a stick, dug at the ancient lava. In less than a minute she’d hollowed out a small tunnel. She flicked the stick away and reached in and brought out a handful of the unweathered rock. She tilted her hand to the light and studied the clean glittering blackness, then grunted and spilled the crumbs at her feet. He sensed her assembling words.

‘This’s from an old volcano, yeah?’

‘That’s right,’ he said not looking at her, but hearing he’d not quite kept the surprise from his voice. ‘Very old, why it’s crumbly.’

‘We done volcanoes in science. Ig-something.’

‘Igneous, you’re spot on — volcanic rock. This particular rock’s called basalt.’

‘So …’ she flicked her hand over the spill, ‘how do you make rock into pots?’

He signalled to the young ones to stop scooping. Retaining the mouth of the bag in his hand he swivelled on his soles, but stayed on his haunches. She lacks education, he told himself, not intelligence. Don’t talk down to her.

‘Not pots, glaze — the shiny skin on the pots. Because it’s been melted before, inside the volcano, when it’s heated to a high enough temperature it’ll melt again. And having lots of iron in it, that gives a black glaze. If I’m lucky, with streaks of dark blue or red, or sometimes little brown flecks that look like animal fur.’

‘You sayin you heat it hot as a volcano.’

‘No, no. But hot enough to turn it molten again, yes.’

He saw the word clearly in her face. Bullshit.

‘I don’t use it like you see it here — sorry, I should have explained. I mill it to powder, and I add ash from the fire and another powdered rock called feldspar to help it melt. But a pottery kiln gets very hot.’ A scrunching made him look to his left. Bored, the boy was jabbing a dry fern rib into the loose scree. Emma struck the offending arm, and he stopped. She snatched the rib. Jade had kept her eyes on his face.

‘Hot as an oxy?’

He wondered who the welder was. ‘Not that hot. But thirteen hundred degrees centigrade — if you remember your two scales of temperature. That’s not fireplace-hot, that’s white-hot. A lot of metals melt at that temperature. The kiln has to be bricks.’

She frowned, and he saw his veracity being weighed again. Then she nodded.

‘I think I seen a picture of one. In China or some place.’

‘There’s lots of them in China.’

‘You been there?’

‘I have, yes. To see them. My wife and I.’

He was startled on the return walk when a small hand took his. The boy didn’t risk looking to his face for consent. He gripped back and shortened stride, coughing to swallow away the tightness in his throat. He couldn’t, and finally had to pretend to sneeze so he could wipe his eyes. He thought he must have held a child’s hand since Michael, but couldn’t think whose child. When the path squeezed them into single file or became a scramble the boy reduced his hold to a single finger, but didn’t let go.

At the pool he gently broke the tenacious grip. He took from the pack the small notebook he always carried and wrote his name and phone numbers and said if she needed help and couldn’t reach her sister, and she had charge, to ring him. She glanced at the paper, then folded it and zipped it into the top pocket of her windcheater. He began, and stopped, the voice in his head warning that he risked being told it was none of his business. But he had to ask. Where was she planning to go? They couldn’t live here. As he’d expected, she became evasive, said she didn’t know, maybe Blacktown, to an aunt. Her sister was on it.

‘Well, would you ring me? Just quickly, to say you’re safe? And … you’ve probably already thought about this — if one of you gets sick or hurt. It’s a hard walk up from here. You might need help. Even … the police.’

‘No way.’

‘Well sometimes there’s no choice.’

‘That ain’t!’

He backed off. ‘Okay.’

He shook their hands, hers last, said he’d think of them next time he came up the creek.

‘You will anyhow,’ Emma said, ‘cause we broke you that rock.’

‘And I’ll remember again when I put it on a pot.’

The smile she gave him was fleeting but pleased.

He looked back from the boulders where he’d found the wrapper, and they were still standing where the pad met the pool. He looked again when he reached the lip of the gully that would take him from sight, intending to wave. They were gone. It gave him an odd, perplexed feeling to know that this place he’d thought pristine was peopled, had been all along.

His own familiar kitchen felt odd after the ‘kitchen’ he’d not long ago left. He made grilled cheese on toast, sat at the table to eat rather than standing at the window. As he chewed he kneaded his right knee. There would come a day when it would require more than kneading. ‘I’d better get a stockpile before then,’ he said across the table, as if he and Adele were discussing their failing joints. Or pay someone younger to go down for him. It was hardly a ‘secret’ anymore.

He changed into work clothes and carried the ore bag over to the annexe. He poured half the rock into the heavy porcelain jar and added the balls and water, lidded it and lay it on its side on the rollers, and hit the switch to start the slow process of milling granules to slurry.

The teapots were ready. He pulled four handles and lay them on a batt to stiffen. The other four were having lugs and cane. He worked on each pot individually until it was completed, turning the foot and lid, then trimming the spout till it fitted the curve of the body, drilling the strainer holes and attaching it, and handle or lugs. He worked slowly and carefully, not wanting to overcut a spout or excessively thin a lid and have to throw a replacement.

By the time he lifted the last from the banding wheel and studied its profile, lowered it onto its batt, the windowless end of the workshop was in gloom. The dusty alarm clock said five. He’d managed to banish them from his mind as he worked, but now allowed them in. It was dark enough for a fire. She’d be frying the chops. Them and bread, he supposed, and an apple. And perhaps a half-mug of milk each. No,

she’d save that for the muesli, give them cordial. He should have asked what else they had. But what was the point? He hung his apron and went out, rinsed his hands at the tank.

As he neared the steps he heard the distant rhythmic thudding of the drum kit. He stopped to listen. Again the insistent 4/4 which was all the boy seemed to know. He wondered would any of the three down there have ever played an instrument, and, too late to retract the thought, heard Adele’s cross voice, What are you talking about, they’d do music in school! All right, owned then. They would never have owned an instrument. He certainly put in his hours with the sticks, Jerome. Younger than Jade, thirteen, fourteen. Anyway, still with a child’s smooth cheeks and round face. And visibly fed. A language and their ages were about all Helen’s two shared with the three. ‘Well, insofar as they have a roof over their heads,’ he said towards the drumming. ‘But you’re forgetting they’re effectively fatherless.’ How long had the man been gone? Gideon. Five years, it must be. Lucy would be struggling to remember him. He barely did himself. ‘So not so different. Just more comfortable.’

How would the three visit their mother in gaol, and the boy his father, without attracting the attention of the authorities? She’d mentioned an aunt. He hadn’t been able to judge then, couldn’t now, whether the aunt was fiction. His damp hands were cold. He started towards the steps. Did he have kindling? Yes, the basket was nearly full. And the woodbox half. He raised his foot and thought, omelette. He stepped sideways to her herb bed, had to look hard before he made out the parsley.

He was stirring porridge when he heard an engine. He paused the spatula and listened. It sounded heavier than a lost car. He lay the spatula across the saucepan and ran to the lounge room windows and was in time to see pass the gap in the planted fence the back half of a white panel-sided Landcruiser and the word RESCUE. He ran back to the kitchen and turned off the gas, and out to the landing and pulled on his sandshoes.

He slowed when he neared the gap and glided to where he could see through the front line of wattles and not be seen. The cruiser was parked in shade, or in hiding, its nose into the casuarinas. Four men in white overalls tucked into high-laced boots were out and equipping themselves with belts and coils of rope. A metallic voice came from the open door of the cab but none paid it any attention. The tallest of the men adjusted the hang of the bandolier of rope he wore, then slammed the door and locked it. The other three were already walking towards the lookout.

When the four disappeared he sidled out onto the road. He could have spoken to them. But he hadn’t trusted his ability to act the innocent householder. Why was he asking, he’d have seen in their eyes. They might then have asked him, had he seen three kids go past in the last week, kids he didn’t recognise as local. No, better not to have given them any reason to be wondering about him on the way down. Let them believe they were wasting their time.

When he returned to the kitchen his eyes went first to the clock. They were younger, fitter. Forty minutes down, a slow couple of hours of checking the track for prints, maybe as far as Helga Falls, then back up, an hour. Around eleven, then, twelve maybe, depending on their thoroughness. That was another good reason not to have gone over to them. His boot prints were everywhere, and fresh. His belly went cold. There’d be prints at the ford going towards the rotted log, and coming from it! He clenched his hands, pressed them to his chin. ‘Please! Read just that I sat there.’ Even better would be if the lyrebirds had overnight turned all the tracks into a shambles. He stood for a moment in a dither. There was nothing he could do. He started towards the stove — and jumped when the phone rang! ‘Be her,’ he pleaded. Instead Helen Kent said, ‘Russell, are you in the house?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you see we’ve got police over at the lookout?’

‘I did, yes. Rescue. I don’t know why. I haven’t heard anyone’s gone missing. Have you?’

‘No — that’s what I was about to ask you.’

‘We might find out when they come back up.’ But I very much hope not, he added silently.

‘You’re … still coming over?’

He heard her trepidation that he might have changed his mind. Or even forgotten, the preoccupied ‘artist’.

‘If I’m still invited.’

‘Of course you are! By then we might know. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a police vehicle in the street.’

‘Oh, in the past, yes. Not for some time.’

He’d planned to spend the morning throwing another run of bowls, but was too anxious. He worked instead in the annexe, where any and all sounds from the road would reach him. He resieved an ash and limestone glaze he wanted finer. He poured off the top water from yesterday’s milling and tipped the slurry into a plaster bath to dry, then set the second batch to milling. At eleven, not trusting his ears, he walked out to the road. The cruiser was still there. Half an hour later he heard the squeal of a door hinge. He dropped the lid on a bucket and bolted for the gap in the planted fence, near its entrance forcing himself to slow to a walk. His heart, though, was threatening to burst through his chest. He crept to the last line of wattles. Just the four! None was speaking into a radio. The side panels were up, and they were stripping themselves of gear. One said something, and they all laughed. The mood was of men who’d done the job asked and now just wanted lunch and to put their feet up. He backed away till sure he was out of sight, then closed his eyes and stood breathing as she’d once shown him, in through the nostrils, hold, exhale through the mouth. He heard the motor start and doors slam. He stayed where he was until the grind of the heavy engine had faded to nothing.

Lucy opened the door to him. Her hair was freshly washed, and she wore jeans and an ironed yellow sloppy joe, printed on it a young man wearing an electric guitar. There was no name, the man evidently not requiring one to be recognised. He began to ask, thinking to display some interest in the girl’s musical tastes, then realised just in time that all he would be displaying would be the abysmal ignorance of the old.

‘Mum and me are here. Jerome’s doing a sleepover.’

‘Oh. I was going to compliment him on his drumming.’

He knelt and placed the small tissue-wrapped package on the carpet and began to unlace his right boot.

‘You don’t need to,’ she said. ‘We don’t.’

‘I know, it’s habit.’

She shrugged. Despite the sloppy joe she radiated an adultness that brought to his mind the self-possession of Emma. She was, he was guessing, about the same age. But she was chubby-cheeked and clean, her eyelids flawless.

Helen met them at the kitchen doorway. She’d dressed, too, for the occasion, in a sleeved red floor-length gown with swirls of embroidery on the bodice. He searched for the word and, to his surprise, found it, ‘caftan’. He’d not seen one in years, had believed them extinct. Two thoughts collided, where on earth had she found it, and that she tried too hard. He pushed both from his mind and held out the package. ‘A little something.’

‘Ohh! I said bring nothing!’

He saw her glance down and note his socked feet, bite her tongue. The girl was hovering, wanting both to escape and to see what the tissue contained. The kitchen table was set for three, an opened bottle of red at the centre.

‘Friends’ table,’ she said.

He’d eaten here three or four times since Adele died and each time she’d said the same thing.

She rested the package on the cloth and peeled back the petals of paper to reveal the handleless cup, its temmoku a jewel-black against the tissue. The only fault was a halo on the side shielded from the flame, which was underfired, chalky. She turned to him with the cup cradled in her hands. ‘It’s beautiful.’

The girl pulled her hands down to where she could see.

‘It’s not for display, it’s to use.’

She dipped her head. ‘You have my word.’

He was instantly tr

ansported, shouting the same pledge up a cliff to a teenage girl who didn’t understand and wouldn’t accept it. He saw in the woman’s light frown that his absence was visible. He willed a smile. ‘For green tea, I’d suggest.’

Jade, though, was still in his mind. To speak of her without speaking of her he said, ‘I don’t know if you saw the police come back up. I just happened to be out the front. They didn’t seem to have rescued anybody.’

‘I’m sure it’ll be in the dreaded Gazette if it was anything.’ She swept the tissue from the cloth. ‘Now, please — sit — dinner’s nearly ready. Would you pour us a glass? Darling,’ she said to the girl, ‘there’s juice in the fridge, you can help yourself.’

She’d remembered his partiality to merlot. They touched rims and sipped. Then she carried her glass to the island bench and whipped an apron from the towel rail and dropped its loop over her head.

He watched her. He didn’t know her. Yes, he’d sat at his own kitchen table five years ago while she sobbed and raged. But it was with Adele that she’d made the transition from neighbour-in-need to friend. He’d spoken to her weekly when she began coming to the house for lessons. Adele had made a point of bringing her over to the workshop to say hello and, if he was throwing, to sit for a few minutes and watch. When, though, she set up the studio under her house Adele more often went over there, and weeks would pass without he and Helen seeing one another. Adele had kept him informed as to what she was working on, and on her progress, both emotional and artistic. She’d asked if she could watch a firing, and he’d reluctantly said yes. She’d come to two, the second time bringing Lucy. He’d said nothing, but his demeanour had made plain that he didn’t welcome spectators, even discreet ones, and she’d been sufficiently intelligent to read the signs even before he asked Adele to have a word.

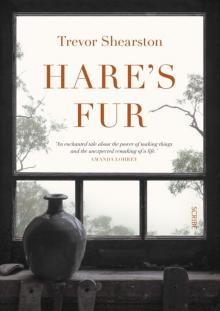

Hare's Fur

Hare's Fur